Is The Oral Torah Divine?

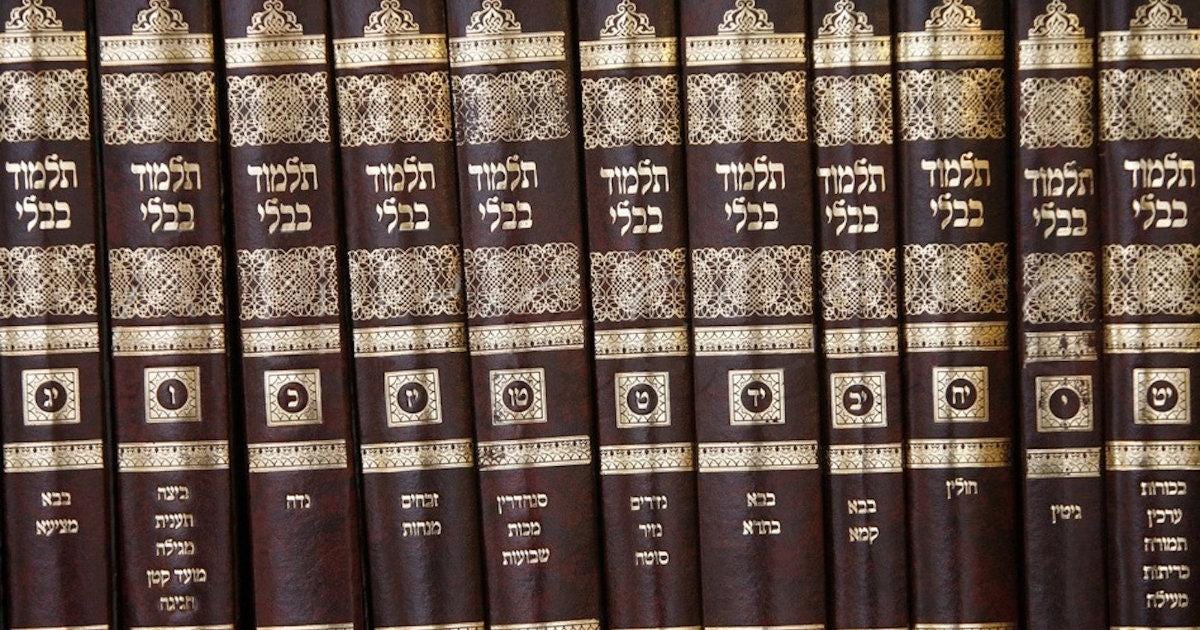

Today’s rabbinic Judaism is governed not just by the Hebrew Scriptures, but also by the Talmud, a written collection of oral traditions. After the destruction of Jerusalem in the first century CE and the exile of the Jewish people, it was feared that Jewish tradition would be lost, and around 200 CE Rabbi Judah the Prince redacted the Mishnah.

The Mishnah is but one component of the Talmud, but it is the component I will discuss in this article. The Mishnah is what is sometimes referred to as the oral Torah. Some rabbinic Jews insist that this oral Torah was delivered to Moses at Sinai, along with the written, and that it was transmitted faithfully over thousands of years of Israelite history until finally written down when at risk of being lost.

As you might imagine, those who believe the Mishnah to be divinely transmitted to Moses ascribe to it a degree of holiness and authority on par with the written Torah. One who wishes to convert to Judaism today, at least to any rabbinic stream of Judaism, must accept, to one degree or another, the binding nature of the Mishnah.

There are other groups of Israelites, such as the Israelite Samaritans and Karaites, who reject the divinity and binding authority of the Mishnah, while not necessarily rejecting all of its wisdom outright. My own perspective on the Mishnah is very similar. This is how I see it:

It was not delivered to Moses at Sinai

It is not divine

It does contain some valuable history and wisdom

It is of Pharisaic origin (the Pharisees are the forerunners of today’s rabbinic Judaism)

It is simply a compilation of rabbinic tradition, interpretations and often opposing viewpoints and arguments over proper practice

It at times directly contradicts the written scriptures and in such cases must be rejected (on those points)

The Mishnah was not transmitted to Moses at Sinai

The written Torah never mentions the existence of a separate oral Torah. Instead, one finds passage after passage that speaks of the written Torah being complete and alone:

and Moses wrote down all the words of YHWH. Early in the morning he built an altar at the foot of the mountain and arranged twelve standing stones – according to the twelve tribes of Israel. (Exo 24:4)

He took the Book of the Covenant and read it aloud to the people, and they said, “We are willing to do and obey all that the LORD has spoken.” (Exo 24:7)

YHWH said to Moses, “Write down these words, for in accordance with these words I have made a covenant with you and with Israel.” (Exo 34:27)

When he sits on his royal throne he must make a copy of this law on a scroll given to him by the Levitical priests. It must be with him constantly and he must read it as long as he lives, so that he may learn to revere YHWH his God and observe all the words of this law and these statutes and carry them out. (Deut 17:18-19)

if you obey the LORD your God and keep his commandments and statutes that are written in this scroll of the law. But you must turn to him with your whole mind and being. This commandment I am giving you today is not too difficult for you, nor is it too remote. (Deut 30:10-11)

Then Moses wrote down this law and gave it to the Levitical priests, who carry the ark of the LORD’s covenant, and to all Israel’s elders. (Deut 31:9)

When Moses finished writing on a scroll the words of this law in their entirety, he commanded the Levites who carried the ark of the LORD’s covenant, “Take this scroll of the law and place it beside the ark of the covenant of the LORD your God. It will remain there as a witness against you, (Deut 31:24-26)

Then Joshua read aloud all the words of the law, including the blessings and the curses, just as they are written in the law scroll. Joshua read aloud every commandment Moses had given before the whole assembly of Israel, including the women, children, and resident foreigners who lived among them. (Jos 8:34-35)

The Mishnah also never claims to be divine, nor do you find anywhere the markers of divine transmission that one finds in the Torah (i.e. “YHWH spoke to Moses, saying …”).

The Mishnah is of late pharisaic/rabbinic origin

Reading the Mishnah, one can see that it is rabbinic in origin. As a sect, the Pharisees date to around the middle of the second century BCE. There are likely some traditions in the Mishnah that carried over from before the Pharisees, but everything in the Mishnah is documented as to how it is understood by rabbinic teachers and sages. Here’s how the Mishnah begins:

From when may one recite Shema in the evening? From the time when the Kohanim go in to eat their Terumah [produce consecrated for priestly consumption], until the end of the first watch – so says Rabbi Eliezer. And the Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until the break of dawn. It once happened that his [Rabban Gamliel’s] sons came from a house of feasting. They said to him: We have not recited Shema. He said to them: If dawn has not broken, you are obligated to recite it. And [this is true] not only in this case; rather, in all cases where the Sages said that [some precept can be performed only] until midnight — their precepts are [still in force] until the break of dawn. [For example:] Burning the fats and limbs [of the sacrifices, on the Temple altar] — their precepts [can be performed] until the break of dawn. And [another example:] all [sacrifices] which may be eaten for one day — their precepts [of eating them can be performed] until the break of dawn. If that is so, why did the Sages say, “until midnight”? To distance a person from transgression. (Mishnah Berakhot 1)

You can see by the highlighted references above that this is a very rabbinic document. Oftentimes there are contradictory understandings, from different rabbis, which are documented together. In these cases, those who hold to the Mishnah as a divine revelation insist that contradictory positions held by two or more rabbinic sages are ALL the words of YHWH, despite the fact that they are incompatible with one another.

The Mishnah contradicts the written Torah

While there is value and wisdom to be found in the Mishnah and the rest of the Talmud, there are also problem areas where direct contradiction to the written Torah is expressed. Let’s look at just a few for illustration.

Rosh Hashanah

Rosh Hashanah means “head of the year”, or the New Year. Mishnah Rosh Hoshanah begins:

The four new years are: On the first of Nisan, the new year for the kings and for the festivals; On the first of Elul, the new year for the tithing of animals; Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Shimon say, on the first of Tishrei. On the first of Tishrei, the new year for years, for the Sabbatical years and for the Jubilee years and for the planting and for the vegetables. On the first of Shevat, the new year for the trees according to the words of the House of Shammai; The House of Hillel says, on the fifteenth thereof. (Mishnah Rosh Hoshanah 1)

Strange that there are four separate New Years. Notice that the “new year for years” is the first of Tishrei. Tishrei is the seventh month of the Hebrew year. How can it be that the new year for years is in the seventh month? There is a holiday on the first day of the seventh month: Yom Teruah!

What does the Torah actually say about the new year?

The LORD said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt, “This month is to be your beginning of months; it will be your first month of the year. (Exodus 12:1-2)

This was at the time of the exodus, in spring, when the barley crops in Egypt were ripe:

Now the flax and the barley were struck by the hail, for the barley had ripened and the flax was in bud. (Exo 9:31)

This is the only new year given in the Torah.

If you were given the task to change the new year to a date as far away from the actual new year as possible, which date would you pick? The first day of the seventh month. Any earlier and you get closer to the beginning of the year, and any later you get closer to the end of the year/beginning of the next. The seventh month, first day is about the farthest you can get from the actual new year.

The truth is that during the Babylonian exile, many foreign customs were picked up by the exiles. Rosh Hashanah was likely one of them. Nehemia Gordon has a great article on How Yom Teruah Became Rosh Hashanah.

Similar issues exist with the counting of the Omer leading up to the feast of Shavuot.

Thanking YHWH for commandments he never gave

When ushering in the weekly sabbath, rabbinic Jewish women will say this blessing, in Hebrew, as they light the traditional sabbath candles:

Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the universe, Who sanctified us with his commandments and commanded us to kindle the sabbath candles.

There is, however, no concept of sabbath candles found anywhere in the Hebrew Scriptures. This is a rabbinic tradition. Dozens of blessings such as this are spoken daily over commandments which YHWH never gave. It may be inspiring and beautiful to live life thanking YHWH so frequently, but for things that he never commanded to be done? An Orthodox Jew is obligated to thank YHWH for commanding him to do many numerous things which were never commanded in the Torah.

Rabbis claim the authority to institute commands and then attribute them to YHWH, using this verse:

You must do what you are instructed, and the verdict they pronounce to you, without fail. Do not deviate right or left from what they tell you. (Deut 17:11)

However, contextually this passages is about a Supreme Court operating at the chosen place, with priests or judges ruling on matters which are too difficult to decide by village magistrates:

If a matter is too difficult for you to judge – bloodshed, legal claim, or assault – matters of controversy in your villages – you must leave there and go up to the place the LORD your God chooses.

You will go to the Levitical priests and the judge in office in those days and seek a solution; they will render a verdict.

You must then do as they have determined at that place the LORD chooses. Be careful to do just as you are taught. (Deut 17:8-10)

These decision would be rendered in accordance with the written Torah, and/or by direct communication with YHWH via the Urim and Thummim. This is not a passage giving rabbinic Judaism the authority to invent new laws!

Bad Cosmology

We read this in Mishnah Tractate Pesachim 94b:

In a discussion related to the structure of the natural world, the Sages taught: The Jewish Sages say the celestial sphere of the zodiac is stationary, and the constellations revolve in their place within the sphere; and the sages of the nations of the world say the entire celestial sphere revolves, and the constellations are stationary within the sphere. Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi said: A refutation of their words that the entire sphere moves can be derived from the fact that we have never found the constellation of Ursa Major in the South or Scorpio in the North. This indicates that it is the stars themselves that revolve in place and not the celestial sphere as a whole, because otherwise it would be impossible for Ursa Major to remain in the North and Scorpio to remain in the South.

Rav Aḥa bar Ya’akov strongly objects to this proof: And perhaps the stars are stationary within the sphere like the steel socket of a mill, which remains stationary while the stones of the mill revolve around it. Alternatively, perhaps they are stationary like the pivot of a door, which remains stationary while the door makes wide turns around it; similarly, perhaps the constellations are stationary within a sphere, and there is an outer sphere within which the sun revolves around all the constellations. Therefore, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s statement is not necessarily true.

The Gemara presents a similar dispute: The Jewish Sages say that during the day the sun travels beneath the firmament and is therefore visible, and at night it travels above the firmament. And the sages of the nations of the world say that during the day the sun travels beneath the firmament, and at night it travels beneath the earth and around to the other side of the world. Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi said: And the statement of the sages of the nations of the world appears to be more accurate than our statement. A proof to this is that during the day, springs that originate deep in the ground are cold, and during the night they are hot compared to the air temperature, which supports the theory that these springs are warmed by the sun as it travels beneath the earth.

None of the above is accurate according to what we know now about our galaxy and the universe, so clearly it is not divine.

Issues of Jew/Gentile relations

The Hebrew word for gentile, goy, simply means “a people”, or “a nation”. The word is sometimes applied to Israel as a nation in the scriptures. However, today the English term gentile has come to mean anyone who is not Jewish. While YHWH chose Israel to be a light to the nations, and a kingdom of priests, this does not mean He is not the God of all mankind, or that non-Jewish people are somehow inferior.

Unfortunately though, the Mishnah does tend to place non Jews on a lower plane when it comes to judicial punishment. Once can find this is several quotes from Sanhedrin 57a:

The Gemara asks: But is a descendant of Noah executed for robbery? But isn’t it taught in a baraita: With regard to the following types of robbery: One who steals or robs, and likewise one who engages in intercourse with a married beautiful woman who was taken as a prisoner of war, and likewise all actions similar to these, if they are done by a gentile to another gentile, or by a gentile to a Jew, the action is prohibited; but if a Jew does so to a gentile, it is permitted? The Gemara explains the question: And if it is so that a gentile is liable to be executed for robbery, and it is not merely prohibited to him, let the baraita teach that he is liable to be executed.

The Gemara answers: Because the tanna wanted to teach in the latter clause that if a Jew does so to a gentile, it is permitted, he taught in the former clause that if a gentile does one of these, it is prohibited. If the baraita were to state that if a gentile does so, he is liable, it would have to state that if a Jew does so to a gentile, he is exempt, because this is the opposite of liable. That would indicate that it is actually prohibited for a Jew to do so to a gentile, and that he is merely exempt from liability, which is not the case. Therefore, the word prohibited is used with regard to a gentile. Therefore, this does not prove that a gentile is exempt from capital punishment.

The above teaches that gentiles robbing gentiles, or gentiles robbing jews, is forbidden, while jews robbing gentiles is not.

The Gemara challenges: But wherever there is liability for capital punishment, this tanna teaches it; as it is taught in the first clause: With regard to bloodshed, if a gentile murders another gentile, or a gentile murders a Jew, he is liable. If a Jew murders a gentile, he is exempt. Evidently, the term liable is used in the baraita.

The Gemara answers: There, in that case, how should the tanna teach it? Should he teach it using the terms prohibited and permitted, indicating that a Jew may kill a gentile ab initio? But isn’t it taught in a baraita that with regard to a gentile, and likewise with regard to Jewish shepherds of small livestock, who were typically robbers, one may not raise them out of a pit into which they fell, and one may not lower them into a pit? In other words, one may not rescue them from danger, but neither may one kill them ab initio. With regard to robbery, the term permitted is relevant, as it is permitted for a Jew to rob a gentile.

The above teaches that a gentile is liable for capital punishment if he murders another gentile, or a jew, but if a jew murders a gentile there is no liability. This is not to say that it is actually permitted for a jew to murder a gentile, but if it happens, he is not liable for capital punishment like the gentile. Additionally, a lower class of jew can also be murdered by another jew without liability.

At the very end of this second segment the permission for a jew to rob a gentile is reiterated.

These ideas are nowhere to be found in the Torah, and should be rejected as foolishness.

Often the claim is made that quotes like these are taken out of context, and to be sure, there are many websites which do that with Talmudic materials in order to falsely paint it in a bad light. However, I would encourage you to read the entirety of this section to confirm that the above quotes are not taken out of context.

In researching this section of the Mishnah, I have come across articles written specifically to counter this information, but I have yet to find any that specifically address the above text to demonstrate it to mean something other than what the plain text seems to say. For example, this page lists Sanhedrin 57a as being part of the (false according to them) claim, but nowhere does their defense actually deal with the presence and meaning of the above text. The argument usually seems to be along the lines of “elsewhere the Talmud prohibits these things so they’re not really permitted.” Unfortunately that does not negate the fact that at least some sages, at some time, subscribed to what is written in Sanhedrin 57a.

The Sefaria website has the entire Talmud online in Hebrew and English for anyone who wants to explore its contents.